[Paper Review] AsymGS: Robust Neural Rendering in the Wild with Asymmetric Dual 3D Gaussian Splatting

Introduction

In this post, I review AsymGS: Robust Neural Rendering in the Wild with Asymmetric Dual 3D Gaussian Splatting by Chengqi Li et al. (McMaster University), published at NeurIPS 2025.

While 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) has revolutionized real-time rendering, it remains fragile when facing “in-the-wild” data. Transient objects (pedestrians, cars) and varying illumination (day/night shifts) break the multi-view consistency assumption, leading to severe floating artifacts.

AsymGS introduces a clever observation: artifacts are stochastic, but geometry is consistent. By training two models in parallel and forcing them to agree, the system effectively filters out noise without relying on heavy, hand-crafted heuristics. The authors also propose a Dynamic EMA Proxy to achieve this dual-model robustness with the computational cost of a single model.

Paper Info

- Title: Robust Neural Rendering in the Wild with Asymmetric Dual 3D Gaussian Splatting

- Authors: Chengqi Li, Zhihao Shi, Yangdi Lu, Wenbo He, Xiangyu Xu

- Affiliations: McMaster University, Xi’an Jiaotong University

- Conference: NeurIPS 2025

- Project Page: AsymGS Website

Background: The “In-the-Wild” Problem

Standard 3DGS assumes that the scene is static and lighting is constant. When these assumptions are violated, the optimization process tries to “explain” the transient objects (like a tourist walking through a landmark) by creating semi-transparent floaters close to the camera.

Existing solutions like NeRF-W, RobustNeRF, or WildGaussian typically use:

- Appearance Embeddings: To handle lighting changes.

- Uncertainty Maps: To downweight pixels that don’t match the model.

However, these uncertainty maps are often learned via heuristics or unstable robust losses, which can lead to confirmation bias—the model “learns” to ignore valid geometry or overfits to the noise anyway.

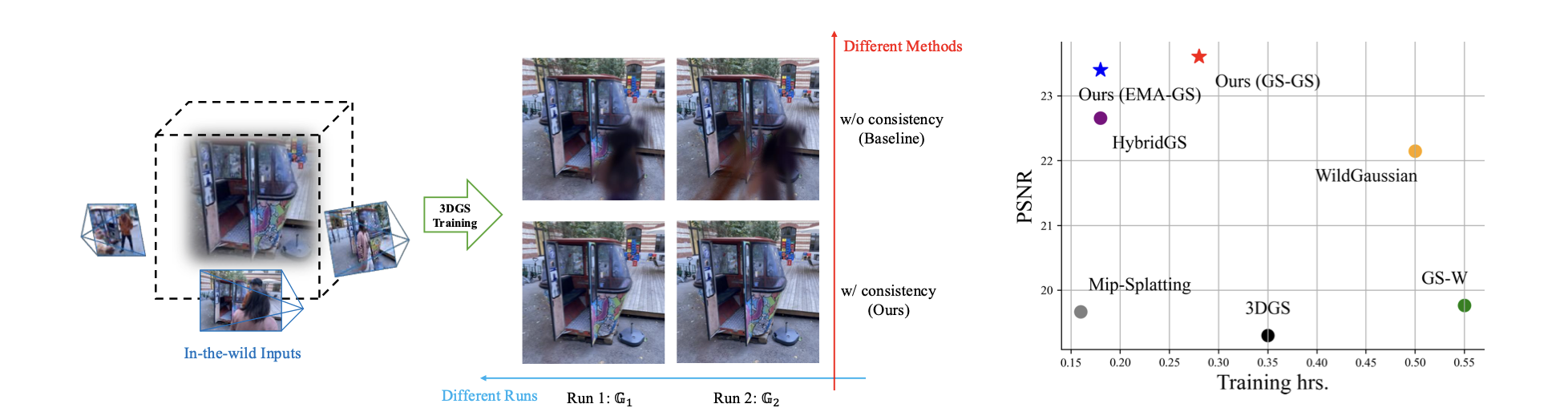

Core Intuition: Stochasticity of Artifacts

The authors observe that if you train two identical 3DGS models on the same noisy data (just shuffling the data order), the valid scene structure converges to the same state, but the artifacts appear in different locations.

This leads to the core hypothesis: If two independent models agree on a structure, it is likely real. If they disagree, it is likely an artifact.

Methodology

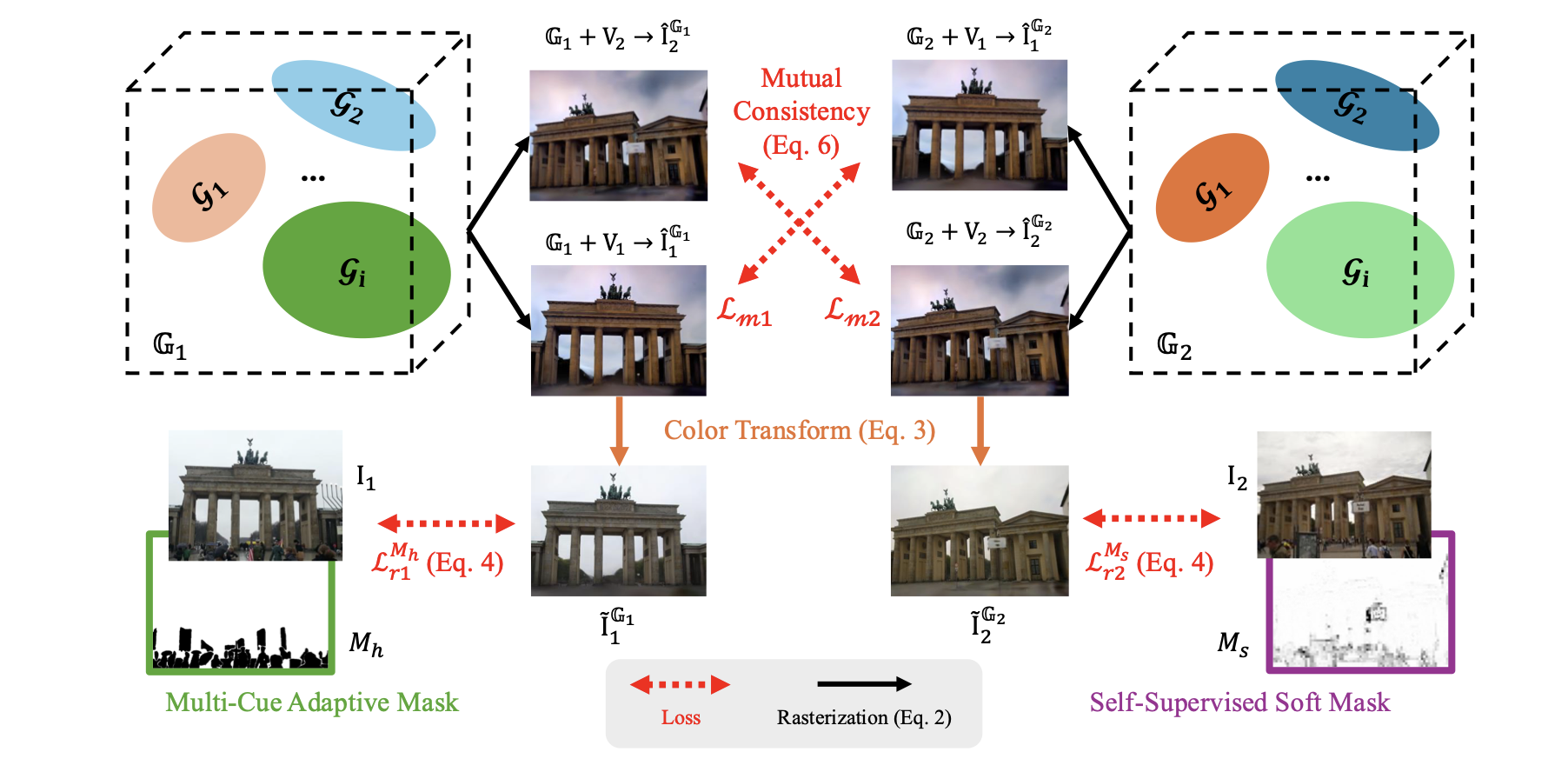

AsymGS proposes a Dual-Branch Architecture where two sets of Gaussians (\(\mathcal{G}_1, \mathcal{G}_2\)) are trained simultaneously.

1. Mutual Consistency Loss

To enforce the consensus, the authors introduce a consistency loss between the renderings of the two models. Crucially, they distinguish between the View-Dependent Rendering (\(\tilde{I}\), which includes transient lighting) and the Intrinsic Rendering (\(\hat{I}\), raw rasterization). The consistency is enforced on the intrinsic rendering to ensure geometric agreement:

\[\mathcal{L}_{cons} = \|\hat{I}_{\mathcal{G}_1} - \hat{I}_{\mathcal{G}_2}\|_1\]2. Asymmetric Masking Strategy

If we simply train two models with the same loss, they might collapse into the same local minima (learning the same artifacts). To prevent this confirmation bias, AsymGS applies Asymmetric Masking. Each model sees the world through a different “filter”:

- Model 1 (\(M_h\) - Multi-Cue Adaptive Mask): A “Hard” mask derived from engineering heuristics. It combines SAM (segmentation), Stereo Consistency (from COLMAP), and Residuals to explicitly mask out potential distractors.

- Model 2 (\(M_s\) - Self-Supervised Soft Mask): A “Soft” mask (\(0 \sim 1\)) that is learned during training. It minimizes the feature distance (DINOv2) between the render and the ground truth:

Because the masks function differently (\(M_h\)is decisive but sparse,\(M_s\) is adaptive but fuzzy), the two models learn different error modes, making their intersection (the consistent geometry) highly reliable.

3. Efficiency: Dynamic EMA Proxy

Training two models doubles the VRAM and compute usage. To solve this, the authors introduce the Dynamic EMA Proxy.

Instead of optimizing \(\mathcal{G}_2\) via gradient descent, it becomes an Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of \(\mathcal{G}_1\):

\[\mathcal{G}_{EMA}^{(t)} = \beta \mathcal{G}_{EMA}^{(t-1)} + (1-\beta)\mathcal{G}_1^{(t)}\]Challenge: 3DGS is dynamic (points are split/pruned). Solution: The EMA proxy mirrors the topology changes of the main model (cloning/splitting) but averages the attributes (position, opacity, SH).

To maintain the “asymmetry” with only one active model, they employ an Alternating Masking Strategy, switching between \(M_h\) and \(M_s\) in alternating iterations.

Results

AsymGS was evaluated on NeRF On-the-go, RobustNeRF, and PhotoTourism.

| Method | NeRF On-the-go (PSNR) \(\uparrow\) | RobustNeRF (PSNR)\(\uparrow\) | PhotoTourism (PSNR)\(\uparrow\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3DGS | 19.30 | 25.05 | 18.13 |

| Mip-Splatting | 19.67 | 25.66 | 18.30 |

| WildGaussian | 22.15 | 28.37 | 24.65 |

| AsymGS (Ours) | 23.60 | 32.39 | 25.62 |

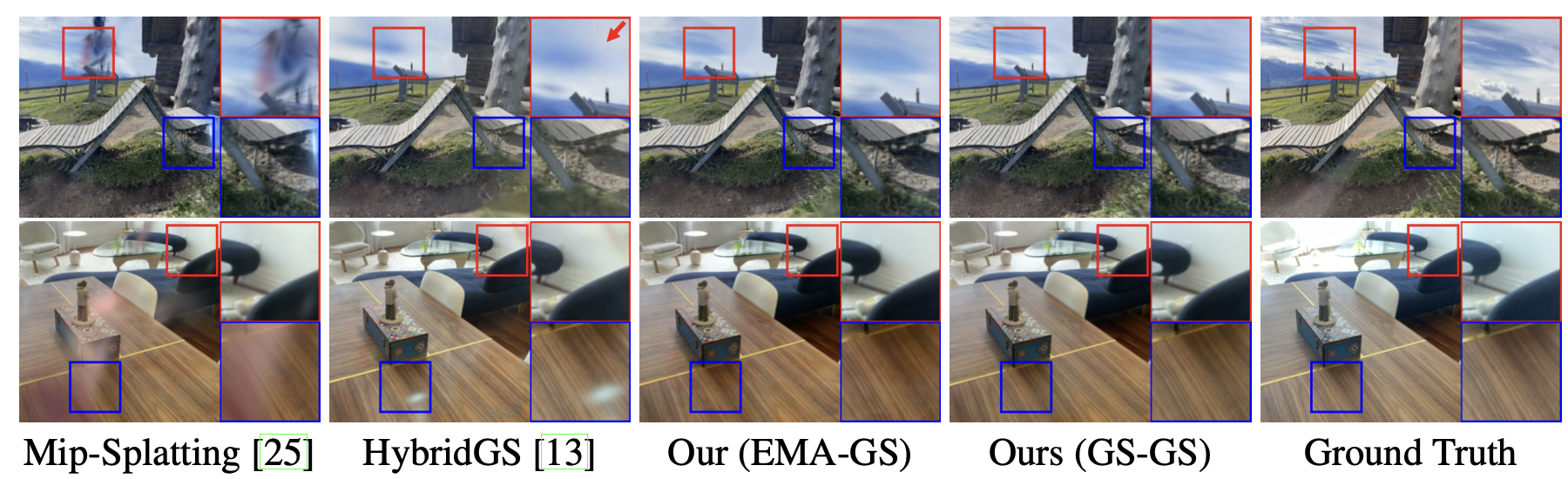

Qualitative Wins:

- Floater Removal: AsymGS successfully removes severe near-camera floaters that persist in WildGaussian and RobustNeRF.

- Detail Preservation: The consistency loss does not over-smooth the background; fine details in static regions (like building facades) are preserved better than in uncertainty-based methods.

Limitations

- Fine-grained Appearance: While the appearance embeddings handle global lighting changes (day/night), the model still struggles with high-frequency view-dependent effects like sharp specular highlights on shiny objects.

- Computational Cost: Even with the EMA proxy, the memory overhead is higher than vanilla 3DGS because the shadow model must be stored in VRAM.

Takeaways

AsymGS provides a robust recipe for handling messy, real-world data in Gaussian Splatting.

Key lessons:

- Stochasticity is a Signal: The fact that artifacts are unstable is a feature, not a bug. Exploiting variance across runs is a powerful denoising signal.

- Dynamic EMA: Adapting EMA to dynamic structures (where the number of parameters \(N\) changes over time) is a significant engineering contribution that could be applied to other adaptive density tasks.