[Paper Review] VGGT: Visual Geometry Grounded Transformer

Introduction

In this post, I review VGGT: Visual Geometry Grounded Transformer by Jianyuan Wang, Minghao Chen, Nikita Karaev, Andrea Vedaldi, Christian Rupprecht, and David Novotny. VGGT is a large feed-forward transformer with minimal 3D inductive biases that ingests one to hundreds of images and, in a single forward pass, predicts camera intrinsics/extrinsics, depth maps, viewpoint-invariant point maps, and dense tracking features. Despite being purely feed-forward, it often outperforms optimization-based pipelines; a brief BA refinement can push it even further. The model also serves as a general-purpose backbone that boosts downstream point tracking and feed-forward novel view synthesis (NVS).

Paper Info

- Title: VGGT: Visual Geometry Grounded Transformer

- Authors: Jianyuan Wang, Minghao Chen, Nikita Karaev, Andrea Vedaldi, Christian Rupprecht, David Novotny

- Affiliations: Visual Geometry Group (University of Oxford), Meta AI

- Conference: CVPR 2026

- Code: VGGT

Background: Geometry Pipelines vs. Feed-Forward Models

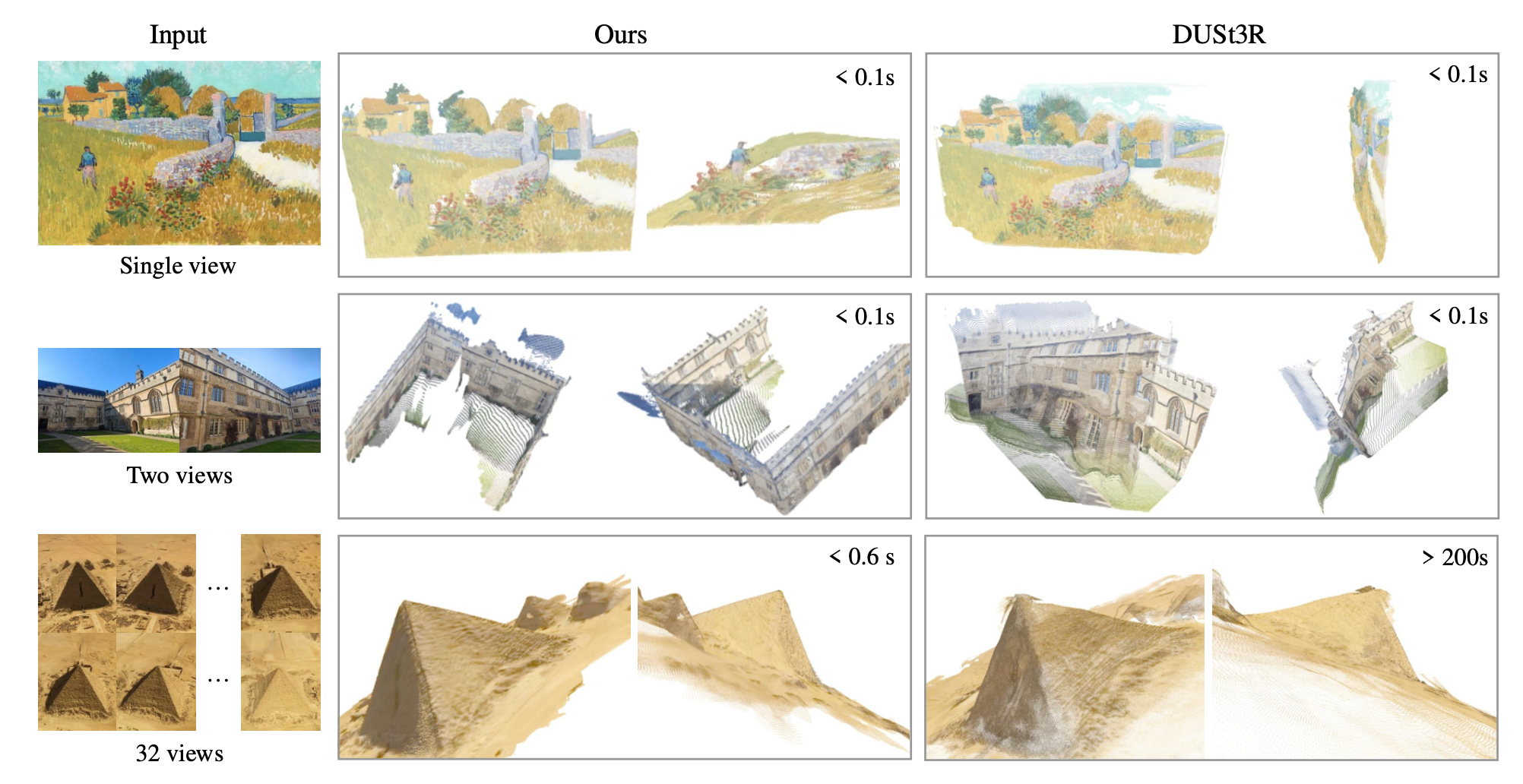

Traditional SfM/MVS stacks (matching → triangulation → BA) deliver accurate geometry but require iterative optimization and careful engineering. Recent neural methods (e.g., DUSt3R/MASt3R) move toward feed-forward 3D prediction, yet are typically pairwise and rely on post-alignment for multi-frame scenes.

VGGT advances this line: multi-view, all-at-once predictions with no explicit 3D representation or heavy geometric modules, trained on a trove of 3D-annotated data.

Problem Definition

Given a sequence of input RGB images that observe the same scene,

\[\{I_i\}_{i=1}^N, \quad I_i \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times H \times W},\]the transformer predicts for each frame:

\[f(\{I_i\}_{i=1}^N) = \{(g_i, D_i, P_i, T_i)\}_{i=1}^N.\]Each predicted component is defined as follows:

- \(g_i = [q_i, t_i, f_i]\) — the camera parameters, consisting of rotation quaternion \(q_i \in \mathbb{R}^4\), translation vector \(t_i \in \mathbb{R}^3\), and field of view \(f_i \in \mathbb{R}^2\).

- \(D_i \in \mathbb{R}^{H \times W}\) — the depth map for image \(I_i\).

- \(P_i \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times H \times W}\) — the point map, where each pixel is associated with a 3D coordinate in the coordinate frame of the first camera.

- \(T_i \in \mathbb{R}^{C \times H \times W}\) — a grid of dense tracking features.

The first camera \(g_1\) defines the world coordinate frame, hence \(q_1 = [0, 0, 0, 1]\) and \(t_1 = [0, 0, 0]\).

All 3D outputs (depths, points, cameras) are expressed relative to this frame.

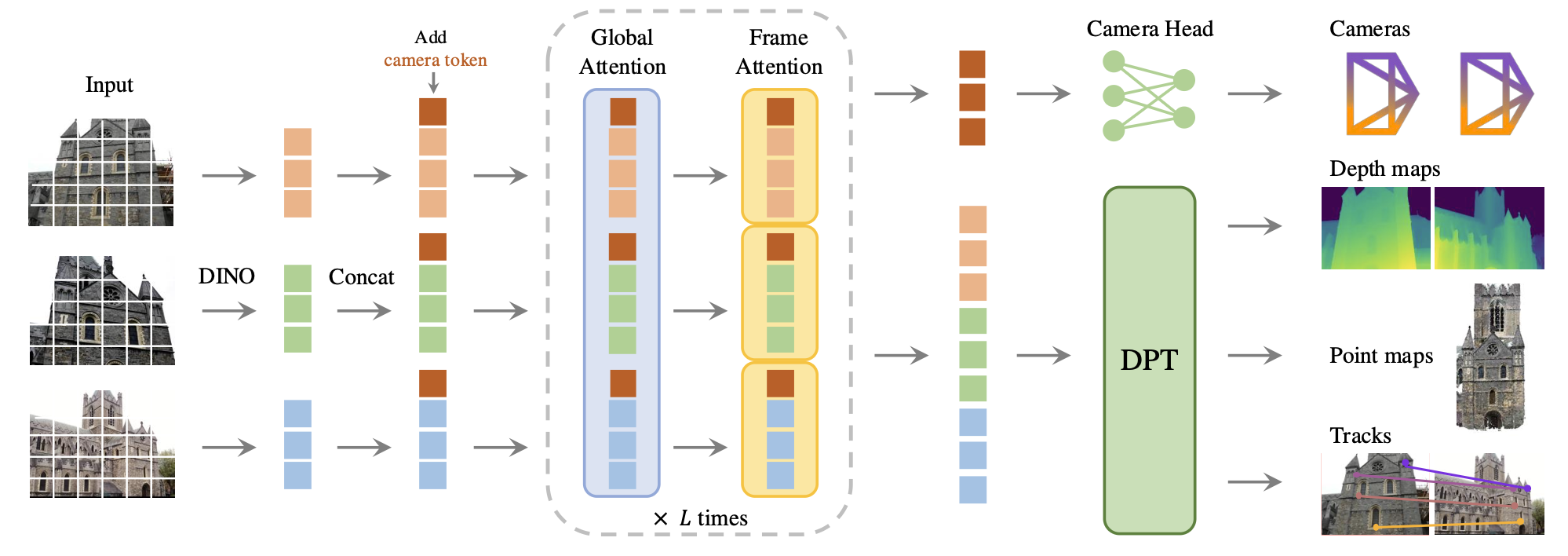

Architecture Overview

1. Tokenization

Each input image \(I_i\) is patchified using DINO, producing a set of visual tokens:

\[t^I_i \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times C},\]where \(K\) is the number of image patches.

To each frame, the model adds:

- a camera token \(t^g_i \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times C}\)

- and four register tokens \(t^R_i \in \mathbb{R}^{4 \times C}.\)

The first frame uses a special set of learnable tokens \(t^g, t^R\) to signal that its coordinate system is the world reference.

The full token set for all frames is concatenated as

\[\mathcal{T} = \bigcup_{i=1}^N (t^I_i, t^g_i, t^R_i).\]2. Alternating-Attention Transformer

The concatenated tokens are processed through an Alternating-Attention (AA) transformer with \(L = 24\) layers.

Each block alternates between:

- Frame-wise self-attention: tokens attend only within their own image (local structure refinement).

- Global self-attention: tokens attend across all images (multi-view fusion).

This alternation achieves a balance between per-frame normalization and cross-view geometric reasoning while avoiding the quadratic cost of dense cross-attention.

The model remains permutation-equivariant for all frames except the first (reference) frame.

After the final AA layer, each frame outputs: \((\hat{t}^I_i, \hat{t}^g_i, \hat{t}^R_i).\)

3. Prediction Heads

(a) Camera Head

The refined camera tokens \(\hat{t}^g_i\) are passed through four self-attention layers and a linear projection to predict:

\[\hat{g}_i = [\hat{q}_i, \hat{t}_i, \hat{f}_i].\](b) Dense Head (Depth, Point Map, and Features)

From the refined image tokens \(\hat{t}^I_i\), the model reconstructs dense feature maps using a DPT (Dense Prediction Transformer) decoder:

\[F_i \in \mathbb{R}^{C \times H \times W}.\]These are passed through lightweight convolutional layers to produce:

- Depth maps \(\hat{D}_i\)

- Point maps \(\hat{P}_i\)

- Tracking features \(T_i\)

The model also predicts aleatoric uncertainty maps \(\Sigma^D_i, \Sigma^P_i\), used to weight geometric losses.

4. Tracking Module

The dense feature maps \(\{T_i\}\) are used by a CoTracker2-style module for 2D correspondence estimation.

Given a query pixel \(y_q\) in a query image \(I_q\), the tracker computes a correspondence trajectory across all frames:

\[T((y_j)_j, (T_i)_i) = ((\hat{y}_{j,i})_i)_j.\]It correlates the sampled feature vector from the query point with all other feature maps and refines them through attention layers to predict consistent tracks.

The tracking head and transformer are trained jointly end-to-end.

Coordinate and Prediction Relationships

The predicted point maps represent absolute 3D coordinates in the world frame:

\[P_i(y) = (X_{i,y}, Y_{i,y}, Z_{i,y}) \in \mathbb{R}^3.\]In principle, these can be derived from depth and camera parameters as:

\[P_i(y) = R_i^{-1} K_i^{-1} [u, v, 1]^T D_i(y) + t_i.\]However, VGGT is trained to predict both \(P_i\) and \((D_i, g_i)\) directly.

This over-complete supervision improves convergence and geometric accuracy, since the network jointly learns camera consistency, depth smoothness, and point-map alignment.

At inference, constructing points from \(D_i\) and \(g_i\) empirically produces cleaner geometry than using \(P_i\) directly.

Training Objective

The model is trained on large 3D-annotated datasets such as CO3Dv2, RealEstate10K, and ScanNet.

Loss terms include:

-

Depth loss

\[\mathcal{L}_D = \|\hat{D}_i - D_i^{gt}\|_1 \cdot (\Sigma^D_i)^{-1}.\] -

Point map loss

\[\mathcal{L}_P = \|\hat{P}_i - P_i^{gt}\|_1 \cdot (\Sigma^P_i)^{-1}.\] - Camera loss for quaternion, translation, and FoV regression.

- Tracking loss over 2D correspondences and visibility.

All terms are jointly optimized as:

\[\mathcal{L}_{total} = \lambda_D \mathcal{L}_D + \lambda_P \mathcal{L}_P + \lambda_g \mathcal{L}_g + \lambda_T \mathcal{L}_T.\]The first frame in every batch is fixed as the reference.

AA allows batching hundreds of frames, enabling stable large-scene training.

Results Summary

-

Camera Pose Estimation (CO3Dv2 / RealEstate10K)

Feed-forward VGGT achieves AUC@30 = 88.2 in 0.2 s (H100 GPU), outperforming DUSt3R, MASt3R, and even VGGSfM.

With bundle adjustment (BA) refinement, AUC rises to 91.8. -

Multi-view Depth (DTU)

Without ground-truth cameras, VGGT attains Chamfer ≈ 0.38, close to models using known intrinsics. -

Point Maps (ETH3D)

Direct point-head output: 0.709 overall Chamfer;

Depth + Cam reconstruction: 0.677 overall, the best accuracy. -

Two-View Matching (ScanNet-1500)

With ALIKED keypoints, VGGT’s tracker exceeds Roma on AUC@5–20 benchmarks. -

Novel View Synthesis (GSO)

A camera-free VGGT variant trained with Plücker rays achieves PSNR 30.4, SSIM 0.949, LPIPS 0.033, competitive with large-view models. -

Dynamic Point Tracking (TAP-Vid)

Finetuning CoTracker with VGGT features boosts metrics (e.g., δₐᵥg^{vis} from 78.9 → 84.0).

Ablations

- Alternating-Attention outperforms global-only and cross-attention backbones by a wide margin.

- Multi-task training (jointly predicting camera, depth, track) achieves better 3D accuracy than any single-task variant.

- Overcomplete supervision—though redundant by definition—proves essential for stability and high accuracy.

Limitations

- Slight pose and depth drift in very long or textureless sequences (can be corrected by a short BA pass).

- Lacks explicit 3D geometric priors, which might limit data efficiency.

- Requires consistent first-frame anchoring during batching.

- Large-scale pretraining demands high compute and large datasets.

Takeaways

VGGT demonstrates that a neural-only feed-forward model can infer full scene geometry—camera, depth, points, and tracks—without explicit optimization.

Its transformer backbone, trained on rich 3D data, generalizes remarkably well and serves as a powerful geometry foundation model.